A study from The Ohio State University is challenging how researchers measure the link between physical activity and memory—revealing that the tools used to track activity may matter just as much as the activity itself.

The research, part of Ohio State’s ongoing FASTER study (Fitness, Aging, Stress, and TBI Exposure Repository), co-led by faculty members Scott Hayes and Jasmeet Hayes, explores how different methods of measuring physical activity can affect what researchers can learn about its relationship to memory performance. It also confirms that people who are more active tend to have stronger memory recall.

“Previous research suggests that being physically active can be beneficial for memory performance,” said Olivia Horn, a graduate student researcher at the Buckeye Brain Aging Lab. “But the results vary. Some researchers find a relationship; others don’t. That might be because researchers are measuring physical activity and memory in different ways.”

To test that theory, the FASTER team collected both self-reported and objective data from adults ranging in age from 18 to 87. Participants completed surveys about their activity levels and perceived memory abilities. At the same time, they wore activity-tracking devices—called ActiGraphs—for a week, which offered an unbiased, data-driven look at their actual movement. They also took part in lab-based memory tests and some underwent MRI scans.

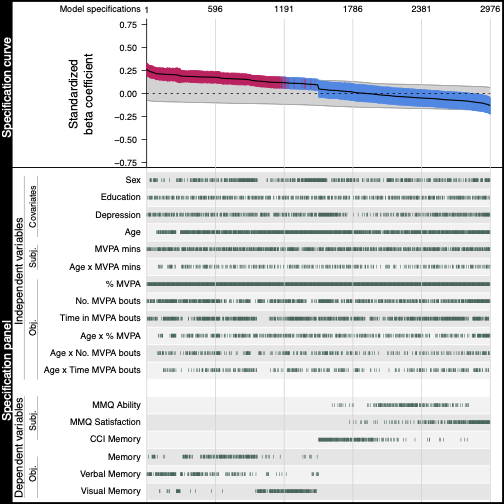

The team then used specification curve analysis to examine the data. This advanced method involved running nearly 3,000 statistical models, along with 600 simulations, to explore how different combinations of variables impacted the results.

That level of analysis was beyond what a standard device could handle.

“I actually crashed my laptop when I tried to run it locally,” Horn said. “Then I learned about the Ohio Supercomputer Center (OSC) and the ability to submit batch jobs. That was a total game changer.”

The project’s complexity—and its reliance on both subjective and objective data—made high performance computing essential.

“It’s important to consider data collection methods,” said Scott Hayes, associate professor in the Department of Psychology at Ohio State and the director of the Buckeye Brain Aging Lab. “The project is unique in that it considered subjective and objective measures of physical activity and memory performance, and used a sophisticated, process-intensive analysis that benefited from the computing power available through OSC.”

What crashed a laptop ran smoothly on OSC’s supercomputers, allowing the team to complete their analysis and reach more definitive results. Horn later presented these findings during a poster session at the Ohio Supercomputer Center Research Symposium, sharing the team’s insights with fellow researchers and students from across disciplines.

The study found a clear, positive relationship between physical activity and memory performance—but only when that activity was measured objectively. Participants who moved more, based on the data from their wearable devices, tended to perform better on memory tests. In contrast, self-reported physical activity didn’t show any correlation with memory, no matter how memory was measured.

“Self-reported physical activity actually wasn’t related to memory at all,” Horn said. “That was true whether we were looking at the objective lab tests or self-reported memory.”

The discrepancy is likely due to several types of bias.

“There’s recall bias—we don’t always remember things correctly. And there’s social desirability bias, where you want to seem like a more physically active person,” Horn said. “Even if it’s unconscious, you might up your number a little bit. We tend to see that people overreport on these questionnaires.”

By using OSC’s high performance computing resources to run a massive number of simulations, the team confirmed that these biases made self-reported data unreliable—at least when it comes to understanding how movement affects memory.

“When you’re studying the relationship between physical activity and memory, future research should rely more on those objective measures,” Horn said. “Data that comes from wearable devices that are less susceptible to biases, for example.”

The study is one piece of a broader effort to examine the many factors that influence brain health over time. FASTER is a collaborative project between the Buckeye Brain Aging Lab and the MINDSET Lab at Ohio State. The larger effort gathers data on cognitive performance, cardiorespiratory fitness, strength, sleep, stress, body composition, and more.

“There are 12 modifiable risk factors that account for about 40 percent of worldwide dementia cases, and physical activity is one of them,” Horn said. “It’s really important for prolonging cognitive abilities over time, which is critical for everyday function—especially for older adults.”

To learn more about the study and its ongoing contributions to brain health research, visit fasterstudy.osu.edu.

Written by Lexi Biasi

The Ohio Supercomputer Center (OSC) addresses the rising computational demands of academic and industrial research communities by providing a robust shared infrastructure and proven expertise in advanced modeling, simulation and analysis. OSC empowers scientists with the services essential to making extraordinary discoveries and innovations, partners with businesses and industry to leverage computational science as a competitive force in the global knowledge economy and leads efforts to equip the workforce with the key technology skills required for 21st century jobs.