Christopher Bartlett and his team at Nationwide Children’s Hospital are using the Ohio Supercomputer Center to better understand genetic links between families with multiple people affected by specific language impairment.

As one of the most common childhood learning disabilities, specific language impairment – a delay in mastering language skills, despite normal hearing, education and intelligence – affects about 5 to 7 percent of all kindergartners.

The exact cause of specific language impairment, or SLI, is unknown, but recent discoveries suggest it has a strong genetic link. Christopher Bartlett, an assistant professor at Nationwide Children’s Battelle Center for Mathematical Medicine and The Ohio State University, and his team, including Stephen Petrill from Ohio State’s Department of Psychology, have made significant strides in understanding heredity’s role.

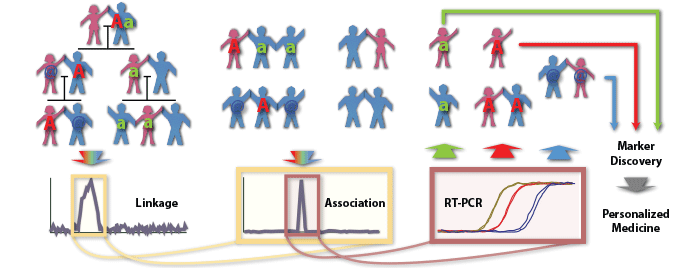

“By using a complex statistical methodology, called posterior probability of linkage, we examined the DNA of families with multiple people affected by SLI,” Bartlett said. “This type of analysis enables us to look at how two genes interact and many other possible genetic architectures.”

To date, the research team has made four important contributions to this research space:

They found strong evidence of a genetic variation associated with SLI on the human chromosome 13q21, and characterized how it affects language, reading or both.

To examine the hypothesis that SLI and autism share genetic causes, they performed the first study that required both disorders be present in each family they studied.

Bartlett’s team furthered the development of the underlying computational and statistical genetic methods for disease gene discovery.

They discovered a modifier gene effect that implicated working memory in developmental language impairments.

Bartlett and his team are extending these successes through genome scans collected from new families. Additionally, they are developing and testing the multivariate statistical approaches to further understand the relationship between implicated genes and language ability – and will again be using the Ohio Supercomputer Center for the computationally intensive calculations. In fact, during the current two-year study, they will use 250,000 resource units – an aggregate measure of the use of CPU, memory, and file storage – to examine about 15,000 gene expression levels in 1,083 people.

“The memory and multicore processors available at the Ohio Supercomputer Center are a must,” Bartlett said, “as the scans typically involve millions of likelihood calculations at thousands of genetic positions across the genome. It would be too slow and, therefore, impossible to conduct this research without supercomputers.”

The goal is to translate this basic science into clinical applications, Bartlett added, in the hopes of earlier identification in patients, earlier intervention, and, ultimately, better outcomes for children affected by this disorder.

Project Lead: Christopher Bartlett, The Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital & The Ohio State University

Research Title: Childhood language impairment and gene expression in the brain

Funding Source: National Institutes of Health